A lovely start to the Baroque Week

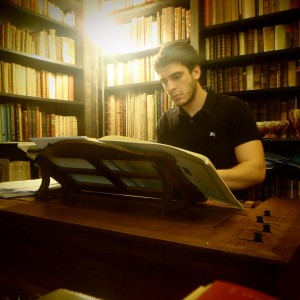

The Victoria International Arts Festival Foundation is the proud owner of a superb harpsichord, which is a model of the 1776 Antunes prevalent in Sicily in the eighteenth century. This wonderful instrument was bought by the Foundation from the prestigious Finchcocks Museum in Kent. Acquiring this instrument has opened up multiple possibilities for the organisers of VIAF one of which is, naturally, organising Baroque concerts. In fact, VIAF, which consists of anything between 36 to 40 concerts each edition, also plans a mini-Festival of Baroque Music within the wider framework of VIAF. These concerts see the performances of great Baroque works, from Bach Suites for violoncello solo, to Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater, and many more. Every year, the organisers are inundated by requests coming from all over Europe and beyond to come and perform in our Festival and it’s a question of being spoilt for choice. The waiting list is long and it’s getting longer. This year, there were 6 consecutive concerts entirely dedicated to the performance of Baroque music. The opening took place on Sunday 10 June with a recital for violoncello and harpsichord by Milan-based performers Rahia Awalom and Gabriele Levi respectively.

The opening work on the programme was Ricercar Primo by Domenico Gabrielli. Gabrielli’s Ricercari are fairly free in terms of compositional structure. Rather than falling into the category of the structured, fugal ricercari of G.B. Antonii, or those of his teacher G.B. Vitali, Gabrielli’s compositions can be grouped into three structural types. The first is the ritornello type. This style contains some elemental subject that returns in a regular manner, thus affording a real sense of organization. The second type is the ‘through-composed’ style. In these ricercari, Gabrielli utilises an almost improvisatory style. The musical ideas seem to naturally arise out of the preceding material, and there is little melodic repetition. In this style, rhythmic ideas and cadential formulas are the main connective tissue. The final formal type used is that of the ‘canzona-type.’ In this style, Gabrielli moves through larger sections, using tempo and meter changes to indicate demarcate sections. This third style is surely a precursor to the method he employed in his continuo sonatas, which are very sectional.

It is the through-composed style that is of greatest concern here, as that is the category that best describes the first ricercar we are listening to this evening. Rahia Awalom has a lovely tone which is most suitable for Baroque works in that while it is rich in texture the performer also managed to control the vibrato throughout her performance, thus enabling her to articulate with clarity and precision. The opening statement of the first five measures comprised the closest Gabrielli comes to providing a theme.This example showed the basic contour that was used throughout the first ricercar. It is a gentle rising, by way of scale steps, followed by some type of large leap, closed with a very basic, if not expected, cadence. The other main, and important feature of this idea is that it commenced on beat two, after a rest. While this rest was the only one that appeared in the entire composition, it served as a guide when finding other points throughout the work where new ideas are beginning. The rest of the piece resembled a written out, free improvisation upon this opening melodic fragment. Gabrielli varies the rhythm, introducing eighth notes in measure 12, and later adds syncopated and dotted rhythms.

The second piece was Carlo Graziani’s Sonata in E Minor op. 2 no. 3, a work in three distinct movements. The name Carlo Graziani has, regrettably, largely been forgotten to all but music historians. Although much is still not known about the details of his life, we do know he was active and successful as one of the rare breed of cellist performer/composers in the late Baroque period.

Graziani’s Cello Sonatas op. 2 (he also has another set of six, op. 3), quite clearly demonstrate the high level of technical abilities the composer must have possessed and his clear understanding of both the capabilities and limitations of his instrument. While they are not showy just for the sake of virtuosity, the rapid cross-string passages, frequent double stops, harmonics, and use of very high registers test the mettle of all who would perform them. The opening Allegretto of the work performed during the evening set the benchmark for such technical difficulties, as it were, and it required an elegant poise, especially in the use of the bow, to extract the liquid fluidity of the phrasing. This elegance seeped through into the following Adagio sempre legato, where the emphasis was on the singing quality of the melodic lines. The final Rondo was delivered as a piece characterised by a buoyant mood and lilting rhythms. Throughout, the two instruments were in constant equilibrium, with the harpsichord producing some very fine finger-work. Throughout the music emerged as a network of counterpoint emerging from the woven tapestry of sound.

Salvatore Lanzetti’s Sonata op. 1 no. 5 was another lovely work. One feature that always impresses the listener is that while Baroque music tends to sound homogenous – as one avid fan in the audience remarked – yet the individual style of the respective composer belongs to him alone. It is an extraordinary technical and musical feat in making the same sound ever new and this is in no small way also to the credit of the performers.

The origin of what we now call the ‘modern’ violoncello lies in seventeenth-century Naples, where the instrument took its present form, playing position and technique. Naples, one of the musical capitals of the world in the eighteenth century, produced a wealth of composers and players favouring the cello: Leo, Pergolesi, Vinci, Durante, Fiorenza, Porpora, and Salvatore Lanzetti. The texture of the opening movement of his Sonata op. 1 no. 5, Adagio cantabile, is finely-wrought and extremely well-crafted, with the melodic lines highly expressive. Although written in the majestic Galant Style, Rahia and Gabriele endowed it with enough excitement to keep the listener on the edge of his seat. The Allegro allowed the composer to engage in more exuberant writing, through which he manifested his technical knowledge of counterpoint and voice-leading. The final Minuet was a lovely piece that has all the contours of a stately dance form, so prevalent in the salons of the time.

Giovanni Battista Pergolesi is a giant of the Baroque period, despite his tragic demise at the age of just twenty-five. In the work performed during the evening, Sonata for Violoncello, Pergolesi seems to anticipate the four-part paradigm of the emerging Classical Symphony as fully exploited by Haydn and Mozart and perfected by Beethoven. Although the term ‘Sinfonia’ in the late Baroque period conformed to its Greek etymology as denoting an ‘agreement of sound’, ‘sounds working in harmony’, it was also used interchangeably with the term ‘sonata’. This four-movement work attests to Pergolesi’s genius in both melodic flair as well as craftsmanship. The opening Comodo allowed the instrument to settle and engage in a beautifully woven melody that required passion as well as control for its expression. The Allegro came across as a typically late Baroque piece, with florid ornamentation together with a range of displaced rhythms. This contrasted starkly with the slow movement, an Adagio, where in typical Italianate style the focus was on the singing quality of the instrument. The final Presto attested to the virtuosity of the player, with extended dynamic and tonal range together with crisp articulation required to bring this piece to a resolute close.

The last two pieces on the programme were two Vivaldi sonatas, yet another point of reference when it comes to Baroque music. Both works were in A minor, RV 43 and RV 44. Antonio Vivaldi wrote a set of six sonatas for violoncello and continuo, written between 1720 and 1730, and published in Paris in 1740 by Leclerc and Boivin. In addition to this publication, Vivaldi wrote at least four other cello sonatas. The manuscripts of two of these are kept in the library of the Conservatoires of Naples, and another is kept in the castle of Wiesentheid.

Although technically both the Sonatas we were listening to this evening may have been intended as teaching pieces at the Ospedale della Pietà as part of the composer’s tenure there, when played on the modern violoncello the performance is likely to be full of Baroque passion, drama and adventure. Vivaldi’s style is unmistakable: evergreen, fresh, sprightly in rhythm, ever new in melodic invention. These two Sonatas followed, largely the same format, a slow movement alternating with a fast one. In both the initial Largo sections Vivaldi sings, and the performers took the hint and greatly exploited it with long sweeping phrases, perfect pauses, and wonderful expression. Melody came natural to them and the sheer inventiveness of Vivaldi’s singing talents never wavered in the face of technical demands. The ensuing Allegro movements were contrasting in style and in spirit which were counterbalanced by another Largo. The ending of both Sonatas made formidable technical demands on the performers and they brought these delightful pieces to a brilliant end.

Throughout, Gabriele Levi on the harpsichord was not in an accompanying role but a partner on an equal footing with Rahia Awalom. There was mutual understanding between the performers, balance was maintained and sustained throughout, and their performance was the finest augur of a week of magnificent Baroque music-making.